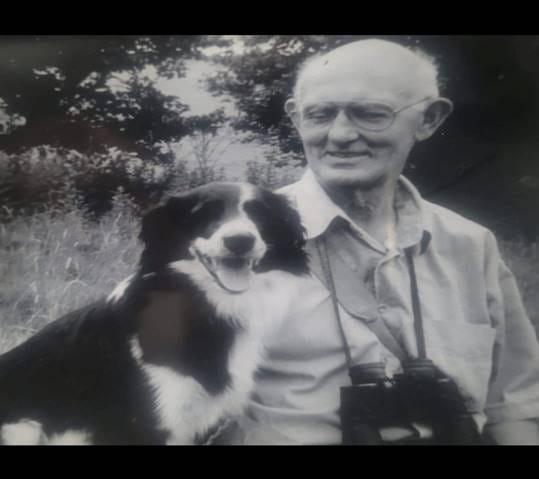

This is BarBar — my grandfather, David Charles Attlee — with Moss, his beloved ‘blueprint’ working dog. The photo captures so much of who he was: quiet, observant, deeply kind. He didn’t need to fill the air with words. He filled it with attention. With care.

And Rosemary, my grandmother, was no different. She offered a calm, wide love — the sort that allowed you to take root. Together, they made a world in which I could just be. No pressure, no rush — only quiet encouragement and a landscape of presence.

They both made me feel like the most important person in the world…..

Some of my most sacred childhood memories come from the long walks I took with BarBar. Out into the countryside, through hedgerows and along sunken paths, where he taught me how to listen. Not just to hear — but to really listen. He’d name birdsong like poetry: blackbird, chiffchaff, willow warbler. Each creature had its voice, its place, its rhythm. He showed me that recognising them was a kind of love.

And then there were the burrows. He once asked me to lie flat on the ground and press my ear, then my nose, to the mouth of a rabbit hole. “What can you smell?” he’d ask. And I would breathe in earth, fur, the faint, wild musk of life. He taught me to look at the brambles for tiny lost hairs, to read the land like a story. I wasn’t just being taught about rabbits. I was being invited into a deeper way of knowing — intuitive, embodied, alive.

That knowing stays with me like a second heartbeat.

He taught me what Goethe called the ‘second imagination’ — not fantasy, but deep seeing. The gift of perceiving not just what things are, but what they mean. And through him, I began to understand what Spinoza meant by looking at nature not as a resource, but as a divine unfolding. A quiet logic of belonging.

One day, standing beside a low wall in a golden field, he held up a handful of wheat. He let the wind carry away the chaff, and showed me the grain resting in his great farmer’s hands. “This,” he said, “is how life is. You lose people, and it hurts. But what remains is what feeds you. The bread of life is in the grain. And you carry that with you.”

That moment shaped me more than I understood at the time. I see it now as the deepest expression of his love — an honest, earthy spirituality. One that mourns, and sows, and waits for growth.

Moss would move quietly beside us — alert, steady. BarBar called him a ‘blueprint’ working dog, and I now think of BarBar himself that way: a blueprint for how to live with tenderness and attention. How to belong to a place, to a rhythm, to each other.

The Butterfly Farmer was born from all of this.

It’s not just a story — it’s my tribute to him. To them. It’s an attempt to bottle that feeling of care, of stillness, of reverence for becoming. A way of saying: this was once held in a grandfather’s hands, and I still feel its warmth.

He didn’t just teach me about birds or rabbits. He taught me that noticing is a kind of prayer. That memory is a kind of bread. That love doesn’t vanish — it transforms.

I miss him.

I miss that world.

But in writing The Butterfly Farmer, I walk beside him again.

This is why I wrote it.

Because I remember what it meant to be loved like that.

Because that kind of love doesn’t die — it becomes part of the field.

Because I hope it lands gently in someone else’s hands, like grain

#hobopoet

I thought about nanny Jordan reading this. Every time something grows in my garden, I think of that time, that world, when nanny Jordan made me feel unconditionally loved.

Wonderful... just wonderful